By Farzad Ghotaslou- Art in Tanzania internship

The Serengeti is a renowned national park in Tanzania. The Great Migration is at its peak from June to September, but animals are abundant throughout the year.

Chances are that you have dreamt of Africa; when you did, you probably dreamt about the Serengeti. Countless wildlife movies have been filmed in the Serengeti, and with good reason: this is the home of the Great Migration and may very well be one of the last true natural wonders on the planet.

Serengeti National Park is a World Heritage Site teeming with wildlife, featuring over 2 million ungulates, 4,000 lions, 1,000 leopards, 550 cheetahs, and approximately 500 bird species, all inhabiting an area of nearly 15,000 square kilometres. Join us on a safari and explore the endless Serengeti plains dotted with trees and kopjes from which majestic lions control their kingdom; gaze upon the Great Migration in awe, or find an elusive leopard in a riverine forest.

Or perhaps see everything from a bird’s-eye view and soar over the plains at sunrise during a hot air balloon safari. Accommodation options come in every price range – the sound of lions roaring at night is complimentary.

It’s the only place where you can witness millions of migrating wildebeest over the Acacia plains, it’s the cradle of human life, and probably the closest to an untouched African wilderness you will ever get. Welcome to Serengeti National Park. Time seems to stand still, despite the thousands of animals constantly in motion.

The magic of Serengeti National Park is not easy to describe in words. Not only seeing but also hearing the buzz of millions of wildebeests so thick in the air that it vibrates through your entire body is something you will try to describe to friends and family before realising it’s impossible. Vistas of honey-lit plains at sunset are so beautiful that it’s worth the trip to witness this. The genuine smiles of the Maasai people give you an immediate sense of warmth inside. It’s magical all year round, or just the feeling of constantly being amongst thousands of animals – it doesn’t matter what migration season you visit the Serengeti National Park.

Serengeti National Park was one of the first sites listed as a World Heritage Site when United Nations delegates met in Stockholm in 1981. By the late 1950s, this area had already been recognised as a unique ecosystem, providing valuable insights into how the natural world functions and demonstrating the dynamic nature of ecosystems.

Today, most visitors come here with one aim: to witness millions of wildebeests, zebras, gazelles, and elands on a mass trek to quench their thirst for water and eat fresh grass. During this tremendous cyclical movement, these ungulates move around the ecosystem in a seasonal pattern defined by rainfall and the availability of grass nutrients. These large herds of animals on the move can’t be witnessed anywhere else. Whereas other famous wildlife parks are fenced, the Serengeti is protected but unfenced. It gives animals enough space to make their return journey, which they’ve been doing for millions of years.

History of Serengeti National Park

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, explorers and missionaries described the Serengeti plains and the massive numbers of animals found there. Only minor details were reported before explorations in the late 1920s and early 1930s supplied the first references to the great wildebeest migrations and the first photographs of the region.

An area of 2,286 square kilometres was established in 1930 as a game reserve in the southern and eastern Serengeti. They allowed sport hunting activities until 1937, after which they stopped all hunting activities. In 1940, Protected Area Status was conferred on the area, and the National Park itself was established in 1951, covering the southern Serengeti and the Ngorongoro Highlands. They based the park headquarters on the rim of Ngorongoro crater.

The original Serengeti National Park, as gazetted in 1951, also included what is now the Ngorongoro Conservation Area (NCA). In 1959, the Ngorongoro Conservation Area was split off from the Serengeti National Park, and the park’s boundaries were extended to the Kenya border.

The key reason for separating the Ngorongoro area was that local Maasai residents realised they were threatened with eviction and consequently were not allowed to graze their cattle within the national park boundaries.

Protests were staged to prevent this. A compromise was reached: the Ngorongoro Crater Area was split off from the national park. The Maasai may live and graze their cattle in the Ngorongoro Crater area, but not within the boundaries of Serengeti National Park.

In 1961, the Masai Mara National Reserve in Kenya was established. In 1965, the location of the Wedge between the Mara River and the Kenya border was added to Serengeti Nationaltherebyk, thereby creating a permanent corridor that allows the wildebeests to migrate from the Serengeti plains in the south to the Loita Plains in the north. The Maswa Game Reserve was established in 1962, and a small area north of the Grumeti River in the western corridor was added in 1967.

The Serengeti National Park was among the first places to be proposed as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO at the 1972 Stockholm conference. It was formally established in 1981.

The name “Serengeti” approximates the word syringe used by the Maasai people for the area, which means “the place where the land runs on forever”.

The Serengeti gained fame after Bernhard Grzimek and his son Michael’s initial work in the 1950s. Together, they produced the book and film “Serengeti Shall Not Die,” widely recognised as one of the most important early pieces in nature conservation documentaries.

On the eastern portion of the Serengeti National Park lies the Serengeti volcanic grasslands, which are part of the Tropical Grassland Ecozone. The grasslands grow on deposits of volcanic ash from the Kerimasi Volcano, which erupted 150,000 years ago, and also from the Ol Doinyo Lengai Volcanic eruptions, which created layers of calcareous tuff and calcitic hardpan soil.

Geography

The plains formed by volcanic eruptions comprise the Park. The primary eruption in its formation was by Kerimasi, a dormant volcano near Lake Natron. The major eruption happened 150,000 years ago. Ol Doinyo Lengai has been active, erupting 15 times since the 19th century, most recently in 2007.

The plains extend from the northeast near Lake Natron to the west as far as Seronera Park. The Park covers 14,750 km2 (5,700 sq mi)[citation needed] of grassland plains, savanna, riverine forest, and woodland

The Park lies in northwestern Tanzania, bordered to the north by the Kenyan border, where it is continuous with the Maasai Mara National Reserve. To the south of the Park lies the Gorongororo Conservation Area. To the southwest is the Liisa Game Reserve, to the west are the Ikorongo and Grumeti Game Reserves, and to the northeast and east is the Loliondo Game Control Area.

Together, these areas form the larger Serengeti ecosystem. The landscape of the Serengeti Plain is highly varied, ranging from savannah to hilly woodlands to open grasslands. The region’s geographic diversity is attributed to the extreme weather conditions that prevail there, particularly the potent combination of heat and wind.

Many environmental scientists claim that the diverse habitats in the region originated from a series of volcanoes, whose activity shaped the basic geographic features of the plain, adding mountains and craters to the land.

The Park is typically described as divided into three regions:

Serengeti plains, an almost treeless grassland in the south, are the most emblematic scene of the Park. Parks are where the wildebeest breed, as they remain in the plains from December to May. Other hoofed animals – zebra, gazelle, impala, hartebeest, topi, buffalo, and waterbuck – also occur in huge numbers during the wet season. “Kopjes” are granite formations that are very common in the region, serving as great observation posts for predators and a refuge for hyraxes and pythons.

In the Serengeti National Park, the Serengeti volcanic grasslands. The Volcanic Grasslands are an edaphic plant community that grows on soils derived from volcanic ash from nearby volcanoes. This plain zone is also famous for granite outcroppings called kopjes, which interrupt the plains and provide habitat for separate ecosystems found in the grasses below.

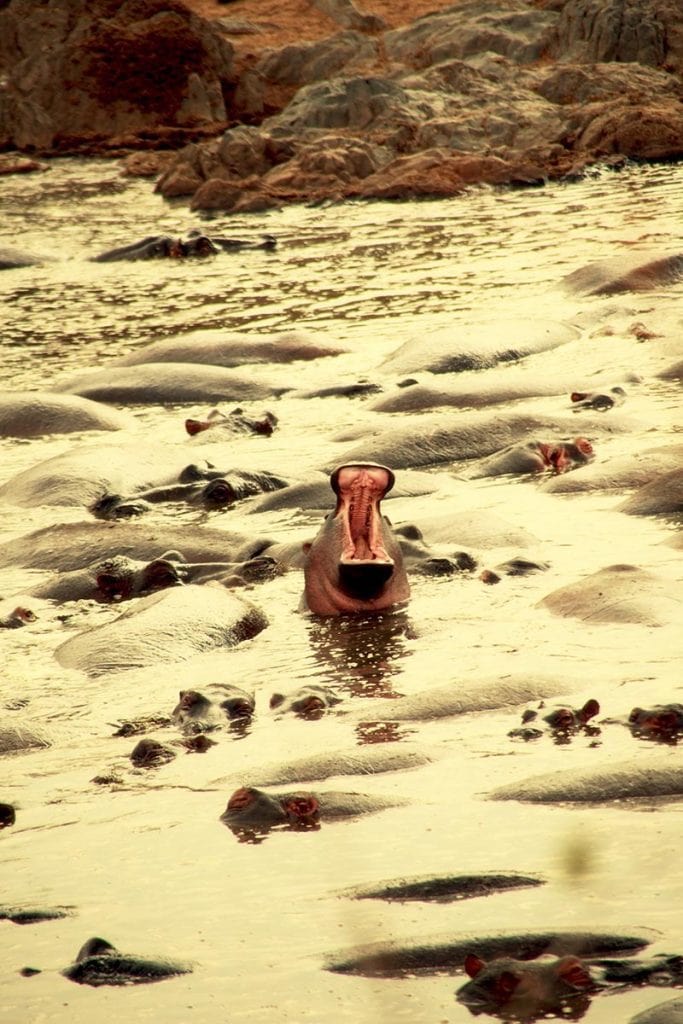

Western corridor: The black clay soil covers the savannah of this region. The Grumeti River and its gallery forests are home to Nile crocodiles, patas monkeys, hippopotamus, and martial eagles. The Grumeti River is famed for its thrilling river crossings during the Great Migration alongside the Mara River. The migration passes through from May to July. There are sometimes rare Colobus Monkeys. It stretches almost to Lake Victoria.

Northern Serengeti: the landscape is dominated by open woodlands (predominantly Commiphora) and hills, ranging from Seronera in the south to the Mara River on the Kenyan border. It is remote and relatively inaccessible. Apart from the migratory wildebeest and zebras (which occur from July to August and in November), this is the best place to find elephants, giraffes, and dik-diks. This plain zone is also famous for granite outcroppings called kopjes, which interrupt the plains and provide habitat for separate ecosystems found in the grasses below.

Human habitation is prohibited in the Park, except for staff of the Tanzania National Parks Authority, researchers, staff of the Frankfurt Zoological Society, and personnel from various lodges, campsites, and hotels. The main settlement is Seronera, which houses most of the research staff and the Park’s main headquarters, including its primary airstrip.

WildPark

The Park is known worldwide for its abundance of wildlife and high biodiversity.

The migratory—and some resident—wildebeest, which number over 1.5 million individuals, constitute the largest of the big mammals that still roam the planet. They are joined in their journey through the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem by 200,000 plains zebra, 300,000 Thomson’s and Grant’s gazelle, and tens of thousands of topi and Coke’s hartebeest.

Masai giraffe, waterbuck, greater kudu, impala, common warthog and hippopotamus are also abundant. Some rarely seen species of antelope are also present in Serengeti National Park, including the common eland, klipspringer, oribi, reedbuck, roan antelope, sable antelope, steenbok, common duiker, bushbuck, lesser kudu, fringe-eared oryx, and dik-dik. Herds support 7,500 hyenas, 3,000 lions, and 250 cheetahs. There are more than 500 bird and 300 mammal species.

Perhaps the most popular animals among tourists are the Big Five, which include:

Lion: The Serengeti is believed to have the largest lion population in Africa, mainly due to the abundance of prey species. More than 3,000 lions live in this ecosystem. Since 2005, the protected area has been designated as a Lion Conservation Unit, alongside Maasai Mara National Reserve, and is considered a lion stronghold in East Africa.

African leopard: These reclusive predators are commonly seen in the Seronera region but are present throughout the Park, and their population is estimated to be around 1,000.

African bush elephant: The herds have successfully recovered from the population lows caused by poaching in the 1980s. They now number over 5,000 individuals and are particularly numerous in the northern region of the Park. The eastern black rhinoceroses are mainly found around the kopjes in the centre of the Park. Due to rampant poaching, very few individuals remain. At times, individuals from the Maasai Mara Reserve cross the park border and enter the Serengeti from the northern section. A small but stable population of 31 individuals is found in the Park. The Park’s buffalo are the most numerous of the Big Five, with around 53,000 individuals.

CaParkores include the cheetah, which is widely seen due to the abundance of gazelle, about 3,500 spotted hyenas, two species of jackal, African golden wolf, honey badger, striped hyena, caracal, serval, seven species of mongooses, two species of otters and the East African wild dog of 300 individuals, which was recently reintroduced (locally extinct since 1991).

Apart from the safari staples, primates such as yellow and olive baboons, patas monkeys, vervet monkeys, and black-and-white colobus are also seen in the gallery forests of the Grumeti River.

Other mammals include aardvark, aardwolf, African wildcat, African civet, common genet, zorilla, African striped weasel, bat-eared fox, ground pangolin, crested porcupine, three species of hyraxes and cape hare.

Serengeti National Park also attracts great ornithological interest, boasting more than 500 bird species, including Masai ostrich, secretary bird, kori bustards, helmeted guinea fowls, Grey-breasted spurfowl, blacksmith lapwing, African collared dove, red-billed buffalo weaver, southern ground hornbill, crowned cranes, sacred ibis, cattle egrets, black herons, knob-billed ducks, saddle-billed storks, goliath herons, marabou storks, yellow-billed stork, spotted thick-knees, white stork, lesser flamingo, shoebills, abdim’s stork, hamerkops, hadada ibis, African fish eagles, pink-backed pelicans, Tanzanian red-billed hornbill, martial eagles, Egyptian geese, lovebirds, spur-winged geese, oxpeckers, and many species of vultures.

The Serengeti National Park is home to a diverse range of reptiles, including the Nile crocodile, leopard tortoise, serrated hinged terrapin, rainbow agama, Nile monitor, chameleon, African python, black mamba, black-necked spitting cobra, and puff adder.

Great Migration

The Great Migration is an iconic feature of the Park and the world’s longest overland migration.[18] Roughly 1.5 million wildebeest migrate north from the south through the Park, north into the Maasai Mara. From January to March (calving season), half a million wildebeests are born, which ensures the herd survives to the following year.

Attacks by the largest lion population in Africa are common this time. In March, the herds depart the southern plains and begin their migration. Giant eland, plains zebra, and Thomson’s gazelle will also join them on the way.[18] In April and May, they will pass the Western Corridor. When this happens, smaller camps must close due to impassable roads.

During the dry season, the herd migrates north to the Maasai Mara, where lush green grass is abundant.

They will have to pass the Grumeti and Mara rivers, though, and 3,000 crocodiles that wait and suddenly lunge at them. For every wildebeest captured by the crocodiles, 50 drown. It is a reason why the Serengeti is so famous. When the dry season ends in late October, they will head back down south to where they started their journey a year earlier. The whole trip is 800 km (500 mi).

Around 250,000 wildebeests and 30,000 plains zebras die annually, usually due to predation, exhaustion, thirst, or disease.

Threats

Massive amounts of deforestation in the Mau Forest region have changed the hydrology of the Mara River, which is its source. The river dried up for the first time in the 2010s. Leopards started cannibalising each other in the late 2010s. It is typical for leopards from the same family to eat each other.

The proposed road across the northern Serengeti

In July 2010, President Jakaya Kikwete reaffirmed his support for an upgraded road through the Parapark’s northern port, linking Mto wa Mbu, southeast of the Ngorongoro Crater, and Musoma on Lake Victoria. While he said the road would lead to much-needed development in poor communities, others, including conservation groups and foreign governments such as Kenya, argued that the road could irreparably damage the Great Migration and the Park’s ecosystem.

The African Network for Animal Welfare sued the Tanzanian government in December 2010 at the East African Court of Justice in Arusha to prevent the road project from proceeding. In June 2014, the court ruled that the plan to build the road was unlawful because it would infringe on the East African Community Treaty, under which member countries are required to respect protocols on the conservation, protection, and management of natural resources. The court, therefore, restrained the government from proceeding with the project.

References:

- World Database on Protected Areas (2021). “Serengeti National Park”. Protected Planet, United Nations Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. “Serengeti National Park”. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Poole, R. M. (2012). “Heartbreak on the Serengeti (continued)”. National Geographic Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- Neumann, R.P. (1995). “Ways of seeing Africa: colonial recasting of African society and landscape in Serengeti National Park”. Ecumene. 2 (2): 149–169. doi:10.1177/147447409500200203.

- Wanitzek, U. & Sippel, H. (1998). “Land rights in conservation areas in Tanzania”. GeoJournal. 46 (2): 113–128. doi:10.1023/A:1006953325298.

- Makacha, S.; Msingwa, M.J. & Frame, G.W. (1982). “Threats to the Serengeti herds”. Oryx. 16 (5): 437–444. doi:10.1017/S0030605300018111.

- Boes, T. (2013). “Political animals: Serengeti Shall Not Die and the cultural heritage of mankind”. German Studies Review. 36 (1): 41–59. JSTOR 43555291.

- Jump up to: a b “About the Serengeti Plains Formation | Natural High”. Natural High Safaris. 6 January 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- Scoon, Roger (2018). Geology of National Parks of Central/ Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania: Geotourism of the Gregory Rift Valley, Active Volcanism and Regional Plateaus. Springer. pp. 69–79. ISBN 9783319737843.

- www.olduvai-gorge.org. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Wikipedia

- Serengeti.com